(Yale Press Release)

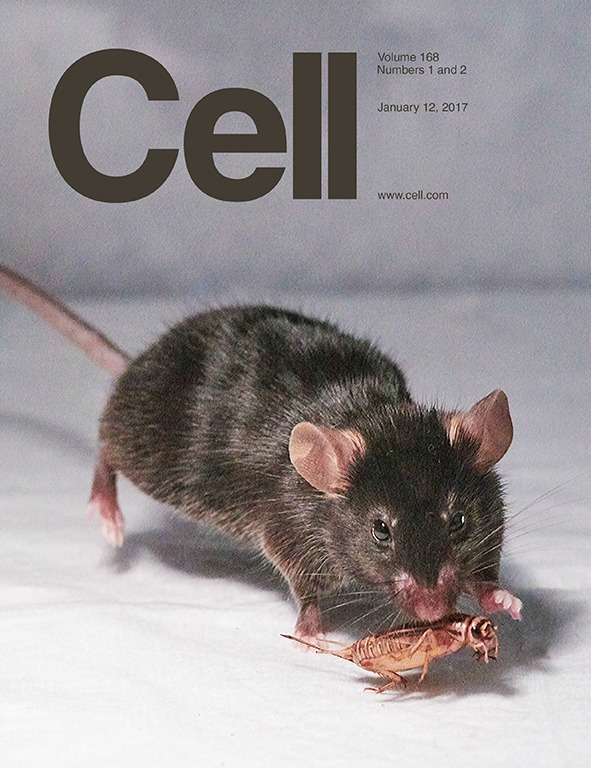

Activating these neurons in living mice prompt them to pursue never seen before prey and to bite everything in their path, even sticks and bottle caps, the researchers report in the January 12, 2017 issue of the journal Cell.

“This area, the central amygdala, seems to allow the animal precise control over the muscles involved in pursuing and capturing prey,’’ said Ivan de Araujo, associate fellow at The John B. Pierce Laboratory, associate professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine, and senior author of the paper.

In their experiments, de Araujo and colleagues used light-based technique called optogenetics to specifically activate neurons of the central amygdala, an almond-shaped structure involved in emotion and motivation. They found that one set of neurons prompted mice to pursue moving objects, while a second set of neurons seemed to activate jaw muscles involved in biting.

Normally behaving lab mice “jump on inanimate objects and bite them” when both sets of neurons are activated, de Araujo said. Activating these neurons also increased the efficiency with which mice hunt and capture live insects, in addition to make them pursue and attack animate toy insects. The two sets of neurons seem to act as relay stations that trigger hunting behavior after the animal detects visual signals of nearby moving prey.

These areas of the amygdala are preserved in almost all vertebrates, attesting to their importance in evolution. Interestingly, these regions seem to be absent in brains of some species such as lampreys, which have no jaws, de Araujo noted. His lab studies feeding behaviors of mice in the lab but felt “we needed to truly understand how an animal pursues food in a natural environment.”

Read the full study published in Cell.

http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/01/12/509487126/flipping-a-switch-in-the-brain-turns-lab-rodents-into-killer-mice

http://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/killer-mice-show-where-hunting-instinct-starts-brain-n706361

http://www.nature.com/news/lasers-activate-killer-instinct-in-mice-1.21292

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2017/01/12/scientists-used-light-to-turn-mice-into-stone-cold-killers/?utm_term=.ca4b96f27af8

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jan/12/scientists-use-light-to-trigger-walking-dead-killer-instinct-in-mice-optogenetics

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/01/lasers-turn-mice-lethal-hunters

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/d-brief/2017/01/12/kill-switch-mice/#.WHg8MFUrK70

https://www.newscientist.com/article/2117842-mice-turn-into-killers-when-brain-circuit-is-triggered-by-laser/

http://elpais.com/elpais/2017/01/11/ciencia/1484139663_747528.html

http://www.latimes.com/science/sciencenow/la-sci-sn-mice-hunters-brain-20170118-story.html